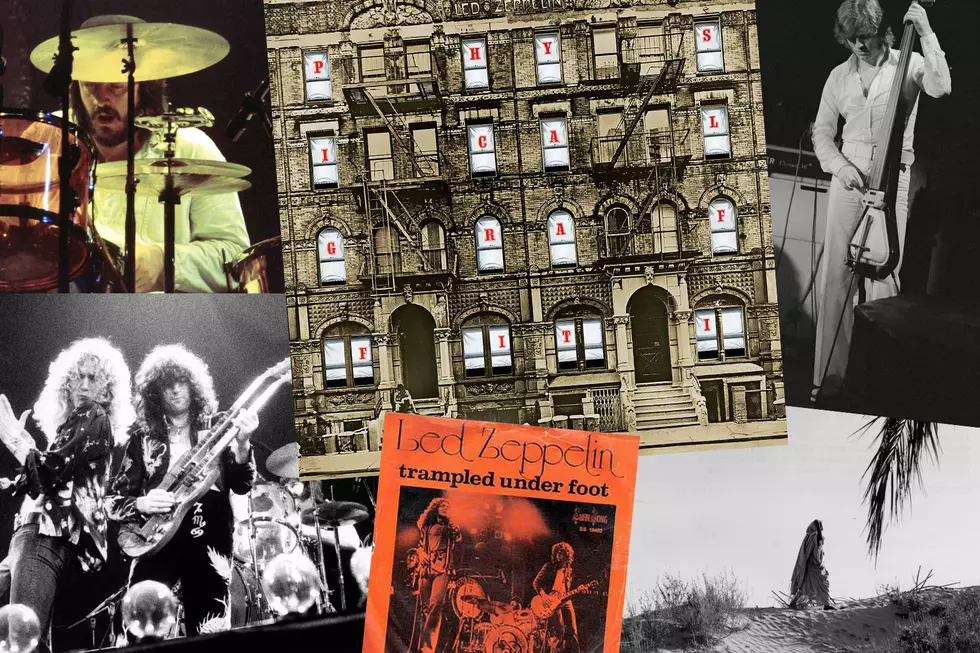

Led Zeppelin’s ‘Physical Graffiti': A Track-by-Track Guide

Led Zeppelin's gloriously bloated sixth album, the 1975 double LP Physical Graffiti, followed its predecessor by nearly two years — an almost unthinkable stretch of dead air for the decade's definitive rock band. But it wasn't due to a lack of inspiration.

The quartet wrapped its North American Houses of the Holy tour in July 1973, and within four months, the members ventured back to the Headley Grange rehearsal and recording spot in Hampshire, England, where they'd previously tracked their landmark fourth record. Guitarist Jimmy Page and drummer John Bonham were fully locked in, already laying down the basis for their eventual anthem "Kashmir." But that vibe wasn't permeating their whole camp: Multi-instrumentalist John Paul Jones, frustrated with touring, nearly quit the group altogether.

After several months off, the refueled Zeppelin restarted the sessions. "I was basically musically salivating on the way there," Page told Rolling Stone in 2015. And they wound up tracking eight new songs, the foundation of the most freewheeling, sonically fascinating album in their catalog. From the string-assisted splendor of "Kashmir" to the ribald funk of "Trampled Under Foot," they weren't just tiptoeing into new territory — they were reveling in it. “All of us knew that it was a monumental piece of work, just because of the various paths that we’d trodden along to get to this," the guitarist recalled. "It was like a voyage of discovery, a topographical adventure.”

The only problem? They had enough material for three sides of music but not a fourth — so to flesh out a second disc, the band raided its archives, rounding out the track listing with unused material that pushed the Zeppelin sound even further away from its trademark hard rock. Let's explore them all in this track-by-track guide to Physical Graffiti.

"Custard Pie"

Robert Plant cranks up the sexual bravado and bluesy swagger to the max on Physical Graffiti's opener, barking out cheap innuendo over Page's tightly coiled riff, John Bonham's booming drums and John Paul Jones' funky Clavinet-and-bass combo. The singer even throws in a harmonica solo, rounding off a classic full-band showcase. But looking back, Plant was never fully satisfied with the track.

"On 'Wanton Song' and 'Custard Pie,' there are things that I can hear that are almost unfinished," he admitted in the 2018 book Led Zeppelin by Led Zeppelin. "Hindsight is a cussed bedfellow, but it's great to fly in the face of it all and meld something tangible, a kind of union between the intent of the much and some sort of vocal release. ... Some songs are finished, some songs aren't. Even now."

Led Zeppelin never played this one live, unless you count the informal, partial reunion — staged one decade after Bonham's death — at the 1990 wedding of the late drummer's son Jason.

"The Rover"

"The Rover" is a fitting title for this bruising blues-rocker, which took time rounding into shape. Page and Plant recorded a hilariously sloppy acoustic demo at Headley Grange in 1973, but they reconstructed the tune into its greasy electric arrangement during the Houses of the Holy sessions (alongside "Black Country Woman" and "D'yer Maker"). After it didn't make the final cut of that LP, Led Zeppelin revived "The Rover" for Graffiti with some remixing and fresh overdubs. (The sleeve credit "Guitar lost courtesy Nevison. Salvaged by the grace of Harwood" is likely a reference to mixing difficulties, using the last names of engineers Ron Nevison and Keith Harwood.)

Despite the rough gestation —and its absence, in full form, from a live set list — "The Rover" became a favorite for both Page and Plant.

"Songs like 'The Rover,' for example, everything worked," Plant said in Led Zeppelin by Led Zeppelin. "The marriage between my lyrical intention, the way I sang it and the way those guys played, there were many times like that. I thought it all worked, there couldn't have been any more that I could have added, or more that I could have taken away to make it work as a consummate finished article."

In 2015, Page praised the song's defining "whole guitar attitude swagger." "I’m afraid I’ve got to say it, but it’s the sort of thing that is so apparent when you hear 'Rumble' by Link Wray — it’s just total attitude, isn’t it?" he told Rolling Stone. "That sort of thing ... is sort of probably in my DNA to be honest with you."

"In My Time of Dying"

Bob Dylan covered this spooky gospel spiritual on his 1962 debut, moaning about death and ascension over a creaky acoustic guitar pluck. But Led Zeppelin transformed the traditional piece into an epic on par with "Stairway to Heaven," stacking riff upon riff into a staggering monolith.

Page took great pride in the song's vast dynamic range — the development from crawling slide-guitar licks to explosive, metallic grooves. Fittingly, it's one of only two tracks on the album (along with the laid-back blues of "Boogie With Stu") credited to the full quartet. "There were no edits or drop-ins or overdubs to the version you hear," the guitarist told Rolling Stone. "This is Led Zeppelin just going for it for an 11-minute song with all the changes in it and everything and the musical map that you have to remember when it goes 1-2-3-4, tapes rolling."

"There was a hell of a lot to sort of remember along the way, but we were up for all of this," he told In the Studio With Redbeard, noting how he deliberately avoided listening to much popular music to preserve his sense of curiosity. This song, "so radical relative to any sort of blues that anyone else had done," defines that originality.

"Houses of the Holy"

Not even Bonham's annoyingly squeaky kick drum pedal can derail this lightning bolt of a song, a leftover from their previous album of the same name. What an embarrassment of riches — only a band at a peak this lofty could shelve one of the catchiest songs in its entire catalog.

Once you dig in Page's stammering funk riffs and Bonham's cowbell-heavy groove, you'll notice the weirdness of Plant's lyrics — a hybrid of his most juvenile sex metaphors and nerdiest fantasy imagery ("There's an angel on my shoulder/In my hand a sword of gold/Let me wander in your garden/And the seeds of love I'll sow").

(Though Bonham's "Squeak King" pedal, a nickname for his Ludwig SpeedKing, is famously audible throughout, it's even more noticeable on other songs, including "The Ocean" and "Since I've Been Loving You." It's almost a charming trademark once your ears adjust.)

"Trampled Under Foot"

Easily the funkiest Led Zeppelin song, "Trampled Under Foot" finds Plant tapping into the same car-metaphor model that Robert Johnson flaunted on 1936's "Terraplane Blues." But the groove is king: The song — which Plant, Page and Jones developed under the working title "Brandy and Coke" — could easily exist as an instrumental, highlighted by the interplay between Bonham's primal thud, Page's stabbing licks and Jones' greasy Clavinet.

The track, which developed from a spontaneous jam, is a perfect showcase for Jones' underrated keyboard work. Many critics have compared it to Stevie Wonder's equally infectious pattern on "Superstition."

"I suppose you could — I wouldn't say that it was a sort of Stevie Wonder-like thing, but other people could," Page told In the Studio With Redbeard. "Actually, the more I think about it, I see why other people do say that."

"Kashmir"

It's the most majestic Led Zeppelin song not named "Stairway to Heaven," and its roots are suitably elaborate. Page developed the track's symphonic arrangement from the seed of a previous piece dating back before the Graffiti sessions, using the cascading guitar fanfare to develop a brand new epic.

"I had a particular idea for a mantric riff with cascading overdubs," the guitarist recounted in Led Zeppelin by Led Zeppelin. "I started playing the riff with John Bonham and we just locked in played it nonstop. It was so infectious, such a delight and just so us. I overdubbed the electric 12-string to what was later the brass parts; I had visualized this piece as being mighty, orchestral, even threatening. When I heard the playback of myself and drums, I knew this was truly innovative. This is the birth of 'Kashmir.'"

Page and Bonham built off the vast reverberations of the drum sound captured in the Headley Grange hallway — the drummer's contribution was so crucial, he wound up with a co-writing credit. Page expanded the stark riffs with brass and strings; Jones added an eerie mellotron; and Plant crafted a vivid lyric inspired by a recent drive through southern Morocco — not, as the title might imply, the Indian region of Kashmir.

"It's one of my favorites," the singer wrote in the liner notes for 1993's The Complete Studio Recordings box set. "That, 'All My Love' and 'In the Light' and two or three others really were the finest moments. But 'Kashmir' in particular. It was so positive, lyrically." Page concurred: "There have been several milestones along the way," he told Trouser Press in 1977. "That's definitely one of them."

"In the Light"

One of Led Zeppelin's most prog-leaning tracks, "In the Light" developed from a similar rehearsal piece called "In the Morning" (available in bootleg form) and another, more polished take later issued as "Everybody Makes It Through" on Physical Graffiti's deluxe reissue. Jones, Page and Plant all contributed to the writing, and it's a true full-band effort — just take the droning intro: a mingling of Page's bowed acoustic guitar, Jones' colorful synthesizer solo and Plant's stacked vocals, which Page told Rolling Stone remind him of "some choral music that I had heard from the Music of Bulgaria." But there's a surprise around every other corner, as a series of winding riffs navigate darkness into light.

In the liner notes for the band's 1993 box set, The Complete Studio Recordings, Plant ranked the song among the band's "finest moments," along with "All My Love" and "Kashmir." Despite their satisfaction, they never played "In the Light" live.

"Bron-Yr-Aur"

This acoustic guitar instrumental, a moment of calm within the free-for-all of Physical Graffiti, reflects Page's fascination with the British folk revival. And if it sounds a bit out of step with the rest of album, there's a reason — the track dates date to the Led Zeppelin III sessions, and it's named after the Welsh cottage where they wrote much of that record.

Page plays an open C-style guitar tuning, his dreamy fingerpicking accentuated with huge dollops of reverb. "It's a C[-type] tuning but not a C tuning," he noted in 2010's Led Zeppelin - III Platinum Album Edition: Piano/Vocal/Chords. "I made it up."

"Bron-Yr-Aur" — their shortest-ever song at a little more than two minutes — never became a live staple, though Led Zeppelin played it for a brief period during the acoustic set on their sixth American tour in summer 1970. More famously, it appeared on the soundtrack to their experimental 1976 concert film, The Song Remains the Same.

"Down By the Seaside"

Few Led Zeppelin songs qualify as "breezy," but here's an exception. Page and Plant first wrote the laid-back "Down By the Seaside" as an acoustic number in 1970, later reworking it as an expanded electric cut during sessions for their fourth LP. It's obvious why they left it on the cutting-room floor for five years — what song could this have possibly knocked off III, IV or Houses of the Holy? But it makes sense within the eclectic stew of Physical Graffiti. Zeppelin never played it live, but Plant did cover "Seaside" with Tori Amos for the 1994 tribute LP, Encomium.

"Ten Years Gone"

"Ten Years Gone" is a true balance of Page and Plant, weaving the guitarist's cinematic riffs with the singer's introspective lyrics. "There's a number of sections on 'Ten Years Gone' and movements, and I'd already sort of constructed all of this before going in," Page told In the Studio With Redbeard of the song's layered arrangement.

Plant tapped into the track's core wistfulness by drawing on a personal tale of doomed love. "I was working my ass off before joining Zeppelin," he told Rolling Stone. "A lady I really dearly loved said, 'Right. It's me or your fans.' Not that I had fans, but I said, 'I can't stop, I've got to keep going.' She's quite content these days, I imagine. She's got a washing machine that works by itself and a little sports car. We wouldn't have anything to say anymore. I could probably relate to her, but she couldn't relate to me. I'd be smiling too much. Ten years gone, I'm afraid."

"Ten Years Gone" become a live favorite, but, like many of Zeppelin's more elaborate pieces, it proved difficult to replicate. In an effort to flesh out the tune, Jones played a triple-neck instrument with a six-string guitar, 12-string guitar and mandolin, all while playing bass pedals with his feet.

"Night Flight"

Over Page's twangy, luminescent chords, Jones' rippling Hammond organ and Bonham's funky drum groove, Plant recounts the story of a draft dodger fleeing the prospect of war for a train ride into the unknown. The song's nifty instrumental flourishes (see Jones' rapid-fire bass notes around 2:39) offer some forward motion, but it's easy to understand why they shelved it during the sessions for Led Zeppelin IV.

The group never played "Night Flight" live, unless you count a sloppy July 1973 soundcheck during the Houses of the Holy tour. At least Jeff Buckley, a noted Zeppelin devotee, dusted it off two decades later for a solo guitar version found on the deluxe Live at Sin-é LP.

"The Wanton Song"

Before the band began its Headley Grange sessions, Page had already worked out the foundations of several tracks at his home multi-track studio: "Ten Years Gone," "Sick Again," the bulk of "Kashmir" and this funky cut. "The Wanton Song" was one of the first riffs they fleshed out as a band, and Bonham's crunching kick-drum accents elevated the groove to near-classic status.

Looking back decades later, Plant wasn't satisfied with his vocals on the studio version, calling them "almost unfinished" in Led Zeppelin by Led Zeppelin. Perhaps that's why the singer revived the song numerous times over the years, both with Page and as a solo artist. (He even used it to open his set at Bonnaroo 2015.)

"Boogie With Stu"

Ian Stewart — the Rolling Stones session pianist and road manager— revs up this low-key jam, a leftover from the IV sessions. (He also played, more famously, on that album's "Rock and Roll.") Given the hassle that ensued upon release of "Boogie With Stu," not to mention the middling quality of the music, it probably should have remained a castaway.

"Ian Stewart came by and we started to jam," Page told Guitar World in 1993. "The jam turned into 'Boogie With Stu,' which was obviously a variation on 'Ooh My Head' by the late Ritchie Valens, which itself was actually a variation of Little Richard's "Ooh My Soul." What we tried to do was give Ritchie's mother credit because we heard she never received any royalties from any of her [late] son's hits, and Robert did lean on that lyric a bit. So what happens? They tried to sue us for all of the song! We had to say bugger off. We could not believe it. So anyway, if there is any plagiarism, just blame Robert."

"Black Country Woman"

This acoustic lark, originally titled "Never Ending Doubting Woman Blues," opens with production chatter, an airplane passing overhead and Plant requesting that they leave in the noise. No moment better encapsulates Physical Graffiti's "let's get weird" aesthetic than that random intro: Led Zeppelin, aiming to experiment, recorded the song during the Houses of the Holy sessions, hauling their gear into the garden of Mick Jagger's country home, Stargroves. "Black Country Woman" is a bottom-tier Zeppelin cut with a generic blues riff, but Bonham's massive drumming salvages the recording.

"Sick Again"

Outside of the shifting time signature and Bonham's cymbal-heavy drumming, "Sick Again" is one of the most straightforward rockers from this period of Zeppelin history. Somehow Plant's vocal still gets buried in the mix, masking a lyric inspired by encountering very young groupies on tour.

"It's a shame, really: If you listen to 'Sick Again,' the words show I feel a bit sorry for them," Plant told Rolling Stone in 1975. "'Clutching pages from your teenage dream in the lobby of the Hotel Paradise/Through the circus of the L.A. queen, how fast you learn the downhill slide.' One minute she's 12 and the next minute she's 13 and over the top. Such a shame. They haven't got the style that they had in the old days ... way back in '68."

Led Zeppelin Solo Albums Ranked

Why Led Zeppelin Won’t Reunite Again