Rush’s ‘Permanent Waves': The Story Behind Every Song

After wrapping their gloriously overstuffed 1978 prog-rock opus Hemispheres, Rush wisely knew they needed to pull back the reigns.

They'd indulged in every whim: geekily titled conceptual suites ("Cygnus X-1 Book II: Hemispheres"), elaborate instrumental pieces with more sections than minutes ("La Villa Strangiato"), drum kits outfitted with temple blocks and gongs. If you can't top a perfect album, why not switch lanes a bit and sidestep the risk of becoming a cliche?

"We were falling into these patterns of writing — the repetition of these thematic things that occur over a 20-minute span," bassist Geddy Lee told Rolling Stone in 2018. "They were starting to feel too comfortably organized in a way, like we weren’t thinking originally enough. That’s kind of a prog pattern. People associate prog-rock with a challenging style of music, and it certainly can be that. But if you’re starting to fall into past habits and develop a methodology that’s too comfortable, it’s not progressive. I think we started to feel that way by the time we finished that record."

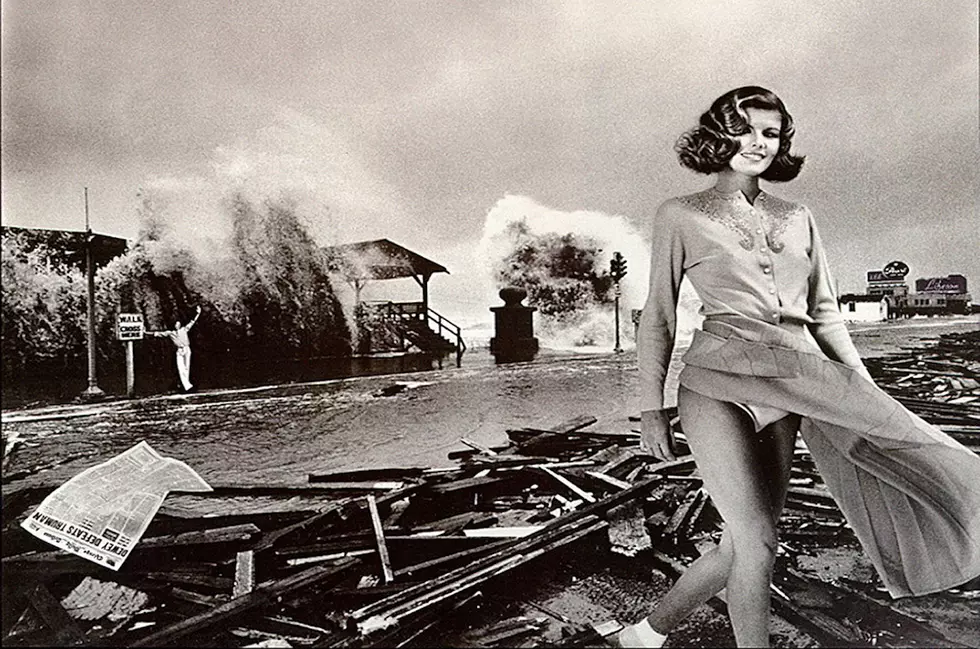

So for their seventh LP, Permanent Waves, the Canadian power-trio — Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson, drummer Neil Peart — consciously trimmed their track lengths, embraced more personal subject matter and nodded to the sleeker sounds of the New Wave scene. (The album title is, fittingly, a playful "poke" at the genre, as Peart told the Chicago Tribune. "There are many New Wave groups we enjoy and respect, like Talking Heads and Elvis Costello and Joe Jackson," he said. "Really, the joke was aimed more at the press, especially the English rock press that is inclined to write off any band that was around last week and go for whatever's happening this week.")

The band felt revitalized after the Hemispheres trek, having booked themselves their first legitimate break from the touring-writing-recording roller coaster. And they found an ideal setting to stay in that frame of mind: a peaceful Ontario farmhouse, where they began working on music in July 1979. The material arrived quickly (including the winding jam "Uncle Tounouse," pieces of which wound up scattered throughout the final album), and Rush eventually nestled into the idyllic Le Studio, which became their de-facto recording base over the next decade.

They emerged with one of their essential works: a tight, punchy — and still sophisticated — record that amped up the catchiness without dumbing down the riffs. To celebrate the album, which came out on Jan. 14, 1980, we dive into the story behind every song on Rush's Permanent Waves.

"The Spirit of Radio"

Surveying the band's full artistic arc, this optimistic anthem is almost quintessential Rush: a hybrid of '70s hard-prog chops and the polished precision that became their calling card in the decade. But without the benefit of hindsight, it's a jarring transition from the grandiose epics of Hemispheres to the bite-sized "The Spirit of Radio."

"I think that was a time when we made a concerted effort to move away from the long thematic songs, especially the full-side songs — albums like Hemispheres — into something shorter," Lifeson told Classic Rock in 2006. And it was a smart move: At a time when few of their prog-rock peers couldn't survive the cultural shift into the '80s, Rush landed a modest worldwide hit, landing their second entry on the U.K. charts.

Fittingly, Peart's lyrics are a tribute to the magic of the airwaves, borrowing its title from the slogan of Toronto station CGNY-FM. (He also throws out a winking allusion to Simon & Garfunkel's "The Sound of Silence" in the final section.) The arrangement is equally playful, from Peart's jazzy cymbal flourishes to the abrupt shift into a reggae-styled breakdown. "We've always played around with reggae in the studio and we used to do a reggae intro to 'Working Man' onstage," Lifeson told Music Express in 1980. "So when it came to doing 'Spirit of Radio,' we just thought we'd do the reggae bit to make us smile and have a little fun."

"Freewill"

There's a lot to unpack on "Freewill," from its profound themes of humanism and religious delusion to its deceptively complex time-signatures. (What other band makes 15/4 and 13/4 sound like the only natural choice?) But everything about it came together strangely quickly: Like both "Jacob's Ladder" and "The Spirit of Radio," Rush wrote "Freewill" within the first three days of writing at Lakewood Farms; they further work-shopped the piece during rehearsals on their stopgap tour in fall 1979, debuting both of the latter tunes onstage — a rarity for the band.

The end product is both playful and intricate, its bright riffs masking the seriousness of Peart's words ("You can choose a ready guide in some celestial voice/If you choose not to decide, you still have made a choice/You can choose from phantom fears and kindness that can kill/I will choose a path that's clear; I will choose free will").

"A lot of mysticism, whether it's astrology or religion ... have you believe that men are evil and must be controlled," the drummer told Jim Ladd in 1980. "And that's the whole premise behind those things that there's something better than man, because man isn't so good and those things have to look after us because we can't look after ourselves. And I believe that might be a nice delusion to hide behind, but when it comes down to it, you make the choices — even if you avoid making the choices by choosing one of these screens to hide behind, you have still made a choice that affects the outcome of your life."

"Jacob's Ladder"

Though "Jacob's Ladder" also emerged from the initial rapid-fire writing surge for Permanent Waves, the band spent a lot of time finessing the soundscapes and lyrics into a final cinematic form. The trio approached the song almost like film directors, starting from the biblical title phrase and developing the structure in what Peart calls a "'cinemative' kind of exercise."

"In my lyrics I've drawn a lot of references from the Bible, because it's a very colorful source of images," he told Jim Ladd. "And I grew up, not religious, but in a religious background, going to Sunday school and taking religious education in school and so on. So, all these things do suggest themselves as metaphors and 'Jacob's Ladder' is a lovely phrase, those two words itself."

The band built the music around that image ("a cloudy sky coming on and then all of a sudden these beams of light"), with Peart retroactively tweaking some lyrics to fit the thematic and textural mood. They wound up with a suitably dramatic track: ominous marching rhythms, swirling synths, Lifeson's multi-layered guitars crashing like thunder.

But not everyone was happy with the results — at least not at first. "I was really bluesed out about the whole thing," Lifeson told Music Express. "'Jacob's Ladder' seemed to be a typical Rush song, a rehash of something we'd done in the past. But then I started hearing the album on the radio and I thought, 'Wow!, this sounds great.' Then I realized I had overreacted to the album and that I had been overly critical of small insignificant things that hadn't affected the overall effect of the record."

"Entre Nous"

The only lyric in Peart's holster heading into the sessions was "Entre Nous," an examination of the social gulfs that separate human beings ("We are strangers to each other full of sliding panels/An illusion show, acting well-rehearsed routines or playing from the heart?/It's hard for one to know"). Lee and Lifeson animated those thoughtful words with crunchy riffs and breezy melodies, and Peart anchored the track with dancing hi-hats and continuously shifting rhythms.

It's an often overlooked entry on the LP — sandwiched between classic singles and bombastic heavyweights, it's sort of an odd man out. The band didn't even play it live until 2007, when it became a staple of the Snakes & Arrows tour. But the song was vitally important in at least one unexpected way: inspiring a teenage Billy Corgan.

"I have this memory of sitting in the basement with my mother. I actually said to her, 'I want to play you a song,'" the Smashing Pumpkins mastermind recalled in the 2010 Rush documentary Beyond the Lighted Stage. "It was very hard to ever get my parents' attention or anything, so it was a big deal. 'Will you please sit here? I want to play you a song.' I played 'Entre Nous,' and I gave her the lyrics sheet because I wanted her to understand that this song was connecting with me on some level. When I was 16 years old, I wasn't as emotionally open — I was very withdrawn. So something about that song allowed me to say, 'Somehow this song is almost like it was written for me.'"

"Different Strings"

This dark ballad features Lee's final Rush lyric, a meditation on withering relationships and fading innocence. (Ironically, for such a mature theme, it kicks off with the line, "Who's come to slay the dragon?" -- which is most definitely the sort of fantasy opener Peart would have written in the '70s.)

Lifeson dominates the track with his atmospheric acoustic fingerpicking, backed by Peart's spidery hi-hat groove, Lee's melancholy bass harmonics and the guest piano of longtime art director Hugh Syme. The only thing wrong with it is the premature fade-out, which kills the vibe of a scorching Lifeson guitar solo. "It reminds me of soldiers sitting around a piano in a smoke-filled pub in England during the war," he told Guitar Player in 1980. "It's the type of solo I really enjoy playing — an emotive, bluesy sort of thing."

"Natural Science"

Rounding out a track listing defined by its accessibility, "Natural Science" is a throwback to the Hemispheres era: a nine-minute, multi-part piece with enough riffs to fill an entire album. Tranquil opening section "Tide Pools" features some expert ambiance: Peart and Lifeson splashed oars in the studio's private lake for the rippling water effects, and they recorded natural mountain echo for the acoustic guitar and vocal. And it's delicious delirium from there, including the manic 7/8 attack on "Hyperspace" and the exploratory rhythmic shifts of "Permanent Waves."

And Rush didn't back down from the daunting arrangement onstage, playing it hundreds of times over the years. "'Natural Science' is always a real challenge to play live," Lifeson admitted in the 2004 book Contents Under Pressure. "There's a lot of intricate, hard playing in it; the tempo's quite upbeat. You sort of set up into it and just go right until the end. So that's always a challenge for all of us. And when we play that well, it really feels great."

Peart's lyrics — which originated from a discarded idea called "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight" (a reference to the King Arthur-era legend) — focus on humanity's struggle to balance nature and technology.

"Obviously the original relationship between men and nature was, you had to tame it to survive," he told Jim Ladd. "And then that became more and more sophisticated and more and more out of hand and finally it became just destruction, you know just for the sake of, of I guess out of fear or something. And now it's become the same thing with science, where people don't understand it and they're afraid of it, and they thing you need to eradicate it in order to control it. I think it needs a lot more of awareness in people's minds about what science is and what it's doing and why. And the fact that science isn't some impersonal thing that's trying to destroy us, it's not an enemy it's something we ourselves created and if it gets out of hand it's our fault for letting it get out of hand. So, what it boils down to really is, we've just gotta take ourselves in hand really more than anything it's we who need the taming."

The Best Song From Every Rush Album

More From 94.9 WMMQ

![Lions’ Frank Ragnow Falls Through The Ice While Fishing [Video]](http://townsquare.media/site/46/files/2020/01/GettyImages-1176613032.jpg?w=980&q=75)