Why Michael Nesmith Hated ‘More of the Monkees’

Most bands spend their whole careers dreaming of a No. 1 album; they might weep with joy if they scored two in less than six months. But the Monkees were not like most bands — a source of long-simmering resentment that reached a boiling point with the release of their wildly successful, and controversial, second LP, More of the Monkees.

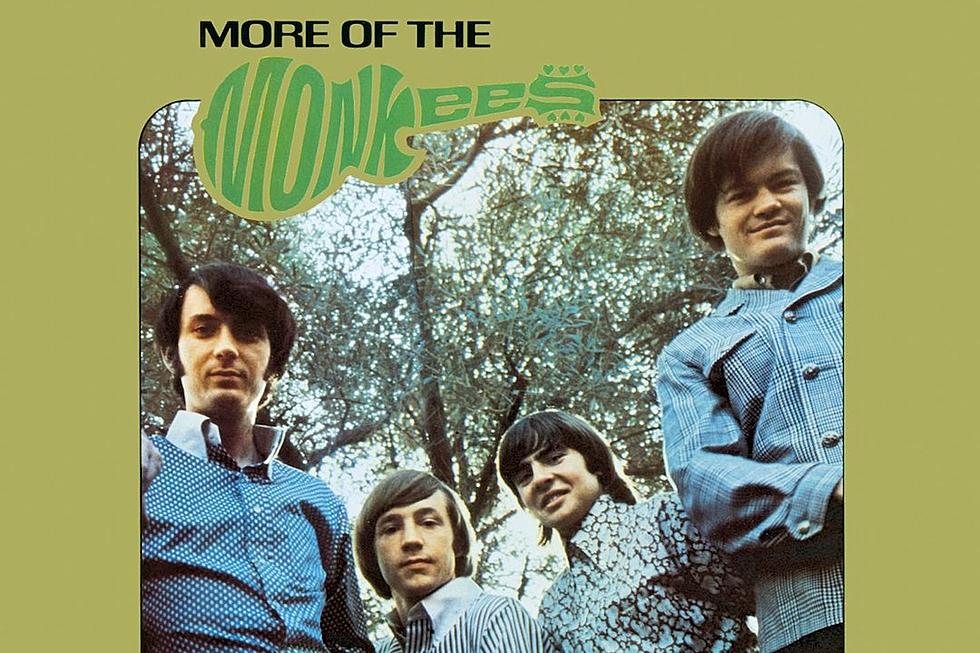

Released on Jan. 9, 1967, More of the Monkees shot to the top of the Billboard 200, displacing the pre-fab pop-rockers’ eponymous debut from the previous October. Buoyed by the chart-topping single “I’m a Believer,” their sophomore record sold five million copies in the U.S. and held the top spot for 18 consecutive weeks, the longest summit for any group in the 1960s. With More of the Monkees, the stateside moptops entered the same league as the reigning titans of the day, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

It’s too bad the band members hated the album.

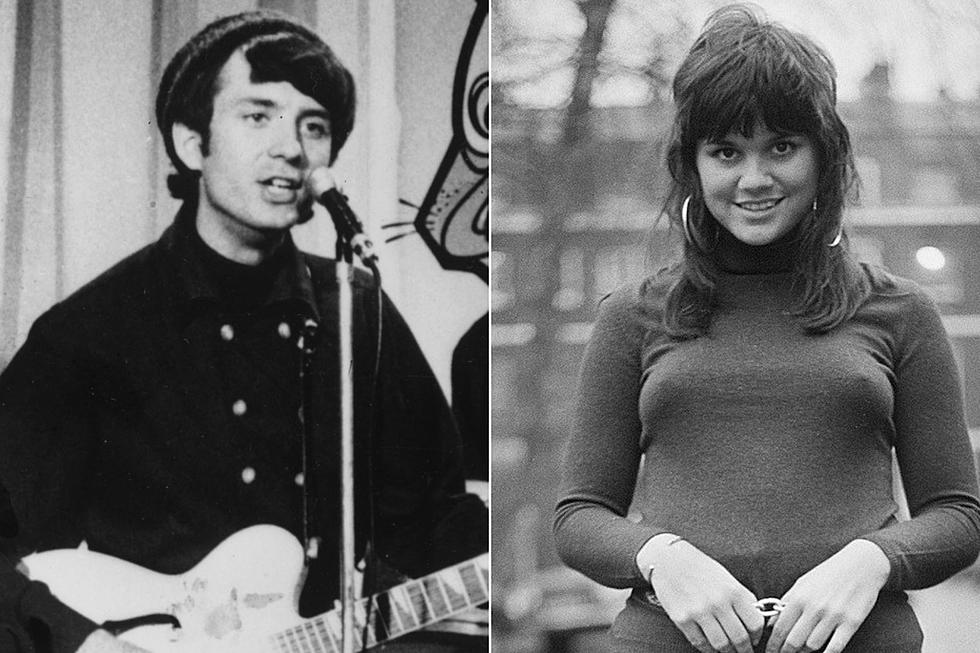

The loudest dissenting voice belonged to Michael Nesmith, the Monkees' driving creative force in the group's early days. Although television producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider had originally conceived the Monkees as a means to cash in on the sitcom of the same name, Nesmith had lobbied for the band members — Micky Dolenz, Peter Tork, Davy Jones and himself — to write their own songs and play their own instruments on record. Music supervisor Don Kirshner rebuffed his pleas and insisted on using outside songwriters and session musicians.

After Kirshner ignored Nesmith's private petitions for more creative freedom, the latter continued the battle in a more public forum: the press. In a revelatory Saturday Evening Post article published in January 1967, Nesmith pulled the curtain back on the band's great (pop-)rock 'n' roll swindle. "The music has nothing to do with us,” he told reporter Richard Warren Lewis. "It was totally dishonest. Do you know how debilitating it is to sit up and have to duplicate somebody else’s records? That’s really what we were doing."

Much to the dismay of the Monkees' press team, Nesmith was far from finished. "Maybe we were manufactured and put on the air strictly with a lot of hoopla," he continued. "Tell the world that we’re synthetic because, damn it, we are. Tell them the Monkees were wholly man-made overnight; that millions of dollars have been poured into this thing. Tell the world we don’t record our own music. But that’s us they see on television. The show is really part of us. They’re not seeing something invalid."

Listen to the Monkees' 'I'm a Believer'

The show caused tensions to escalate further as the Monkees balanced their weekly taping schedule, recording new songs and touring on weekends. Before a Cleveland concert on Jan. 15, 1967, the band caught wind that Kirshner had rush-released More of the Monkees the previous week. They ordered somebody to fetch a copy so they could inspect the damage at their hotel.

Upon retrieving the LP, the Monkees gazed with horror at the cover, which showed all four band members dressed in categorically uncool JCPenney threads from what they thought had been a promotional shoot. Even more ghastly was the back cover, on which Kirshner praised his cadre of songwriters before briefly mentioning the names of the Monkees. “The back liner notes were Don Kirshner congratulating all his boys for the wonderful work they’d done, and oh yes, this record is by the Monkees,” Tork later lamented to Goldmine magazine (as reported by Eric Lefcowitz in his book Monkee Business: The Revolutionary Made-For-TV Band).

The band — particularly Nesmith — reacted even more harshly to the actual contents of the album, which sported occasional production glitches and general inconsistency from one performance to the next, due to an onslaught of session musicians and a whopping nine producers (including Carole King and Neil Sedaka) helming the songs. "I regard the More Monkees album as probably the worst album in the history of the world,” Nesmith later seethed to Melody Maker.

Indeed, More of the Monkees is far from perfect. There are audible guitar flubs on "The Kind of Girl I Could Love," and Jones' cringeworthy murmuring on the treacly "The Day We Fall in Love" is a definitive lowlight of the album (and maybe of any album). Still, Nesmith may have sold the band short in his brutal assessment. Album opener "She" soars on the strength of its lush vocal harmonies and peppy "Hey!" chants, and the bizarre psych-pop spectacle "Your Auntie Grizelda" utilizes Tork's limited vocal range to its fullest extent. Dolenz delivers a ruthless, snarling performance on "(I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone," while "I'm a Believer" is pure pop confection. Nesmith also scores one of the album's biggest wins with his solo composition "Mary, Mary," anchored by its jangly, sing-song lead guitar riff.

Listen to the Monkees' 'Mary, Mary'

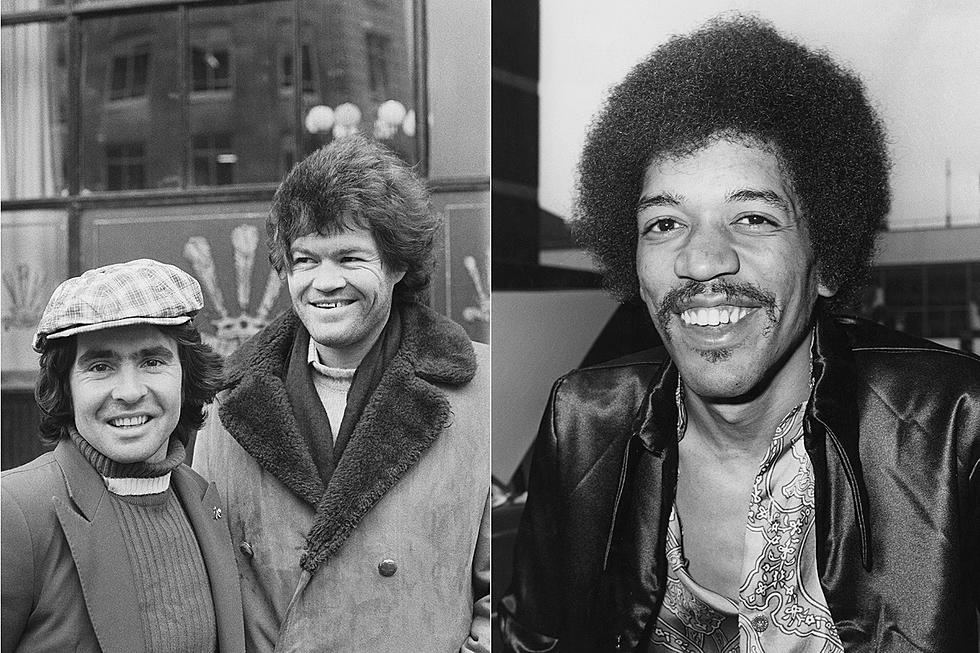

This taste of artistic freedom further emboldened Nesmith to fight for the inclusion of the Monkees' own songs on their albums. One month after More of the Monkees hit shelves, Nesmith attended a meeting at the Beverly Hills Hotel with Kirshner and Herb Moelis, head of business affairs at the band’s record label, Colgems. When Nesmith threatened to quit the Monkees if they couldn't write and record their own music, Moelis suggested he review his contract before issuing any ultimatums. Nesmith, in turn, punched a hole in the wall, turned to Moelis and growled, "That could have been your face, motherfucker."

The outburst paid off. Shortly after the Beverly Hills Hotel dustup, the Monkees fired Kirshner for attempting to issue the Neil Diamond-penned single "A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You" with "She Hangs Out" as a B-side without their consent. The band withdrew the single and replaced "She Hangs Out" with the Nesmith composition "The Girl I Knew Somewhere." The song peaked at No. 39, while its A-side hit No. 2.

Kirshner, for his part, couldn't understand why the Monkees would mutiny when they were raking in cash hand over fist. “The whole thing was a farce,” he said, according Lefcowitz's Monkee Business. “I gave them each a quarter of a million dollars … and really they could have been more appreciative. Every record I put out was number one."

With Kirshner in the rearview, the Monkees were free to express themselves more as musicians and songwriters. They took more active roles in the recording of their next two albums, Headquarters and Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd., both of which topped the Billboard 200 as well. Still, despite these commercial and creative victories, the Monkees never achieved the same stratospheric success as they did on the nearly band-breaking More of the Monkees.

Monkees Albums Ranked

More From 94.9 WMMQ