‘Darkness on the Edge of Town’ at 40: Our Writers Answer Five Important Questions

On June 2, 1978, Bruce Springsteen released Darkness on the Edge of Town. The record, his first since 1975's Born to Run made him a star, arrived after a lengthy lawsuit with his former manager Mike Appel. Although the lyrics didn't directly reference the suit, his bitterness showed in the songwriting. Gone was the cinematic romanticism of his first three albums, replaced by stark portraits of blue-collar American life that would form the basis of Springsteen's writing for the next decade.

Darkness reached No. 5 on the Billboard albums chart, and the tour, where he and the E Street Band made their first ventures into headlining arenas, solidified his reputation as one of the most exciting live acts in rock n' roll. Many of its tracks, including "Badlands," "The Promised Land" and "Prove It All Night" -- as well as the outtake "Because the Night" -- have continued to play an important role in his concerts to this day.

But the 10 songs released represented a fraction of the music recorded for the album, with 57 known titles recorded during the sessions, according to Brucebase. We asked our writers to weigh in on where Darkness stands among the others in Springsteen's catalog and the significance of the outtakes.

Is Darkness on the Edge of Town Bruce Springsteen's best album?

Michael Gallucci: No, that would be Born to Run, for a number of reasons. But Darkness is No. 2. It's the first Springsteen album where he sounds like the Springsteen whose legend was secured around this time.

Nick DeRiso: For me it is, since Darkness on the Edge of Town stands as such a nexus point – for his career and for rock. Stung by very real-world legal issues, Springsteen finally found a way to match the yearning of youth with a grounded sense of adult experience, and it happened toward the end of a period of broad excess when the genre so badly needed it. The production is a wonder of amalgamation, too: He melded the West Coast’s spacious, very polished style with the power and force of Middle American and punk rock.

Dave Lifton: It's very close, but a friend once pointed out that every song on the first side has a corresponding track on the second in the same sequence. "Badlands" and "The Promised Land" are about America, "Adam Raised a Cain" and "Factory" are about father-son relationships and so on. Ever since then, I've thought of it more as two EPs than a perfectly sequenced collection like Born to Run or Tunnel of Love.

Debra Filcman: My personal favorite changes daily, but Darkness on the Edge of Town is consistently among my top three from Springsteen's catalog. I think the excruciating editing process he went through with this album speaks volumes about the focus and quality of the story he was telling here.

Rob Smith: It’s a great record, but I hesitate to call it his best. Born to Run has that wide-open kaleidoscopic feel to it, a sense of both freedom and focus that I don’t think he’s ever quite matched. I think the lyrical concerns he begins to explore on Darkness get boiled down to their essence on Nebraska, and that record’s spooky ambience has always chilled me. I’m also a lover of The River, for its jukebox feel and the looseness of the band. I might flip-flop between that one and Darkness for second runner-up behind Born to Run and Nebraska.

What is the best song on the record?

Gallucci: As the opening song, "Badlands" not only sets the tone for everything that follows, it's also a hell of an introduction to the album with those massive drums barreling into the picture. Every song on the album, more or less, stems from "Badlands."

DeRiso: "Racing in the Street,” because it turns the bombast of what came before completely inside out. If Born to Run was about the desperate desire to be free of your old life, your hometown and every preconceived notion, this album – and, my goodness, this song – was about what happens to those who were left behind. Even the expected early-career “car songs” tend to feature people lost in a cul-de-sac of regret.

Lifton: "Racing in the Street" is my favorite song by anybody. Gina Arnold wrote in Route 666: On the Road to Nirvana about how the brilliance of that song was that, growing up, it was the perfect anthem for her and her friends cruising around town, only realizing later that it had this other meaning. I knew exactly what she means. Somebody had scrawled the lyrics on my desk in my 10th grade Biology class and there's no way on Earth that person could have fully grasped what Springsteen is singing about. I didn't either at the time, and it took years of living to relate to it. I still can't comprehend how Springsteen wrote that last verse, given that he hadn't yet been in a serious relationship.

Filcman: I'm typically torn between "Racing in the Street" and "Darkness on the Edge of Town." The story he tells in the former is so specific and evocative that it really haunts the listener. That's why it's not even surprising when the couple from "Racing" ages a decade or two, and reappears, as I see it, in "Darkness." Springsteen couldn't get them out of his head any more than I could, and the stunning outro gives the listener time to contemplate their fate. It also remains phenomenal to me that early versions of the song didn't even include the little girl he drove away.

Smith: “Racing in the Street” is a great narrative and a great song. The lyrics speak of desolation, lost chances and the things the desperate do just to live, both in the world and with themselves. Springsteen gives those words life and breath, and puts his voice in the middle of it all; there’s no separating it from either the story or the telling of it. The music is stark and brooding -- it’s a keyboard song on a guitar album, and Roy Bittan and Danny Federici refuse to leaven the mood as they might on other songs. Bittan’s piano figure that runs through the song is every bit the match for the lyrics, and then Federici wraps an organ countermelody around the piano. … God, it gives me chills to this day. It’s every sad song you’ve ever heard concentrated into two instruments, speaking directly to the heart.

Darkness is the album where he began tightening his lyrics after three verbose albums. Was it a smart artistic decision on his part?

Gallucci: For sure. His first three albums sorta sound like they were made by three different artists. With Darkness he finally found and settled on his voice. Everything that followed more or less traces the album's template.

DeRiso: What you lost in broad romanticism, Springsteen more than made up for in sharp observation. Clearly, Springsteen was trying to puncture the hype surrounding Born to Run, specifically by making a more serious album. For me, what he ended up doing was finally confirming that hype, completing something that could rightly be called a concept album about the end of the American century.

Lifton: With three years on the sidelines because of the lawsuit with Appel -- an eternity at that time for a musician -- Springsteen has said that he felt he needed to reintroduce himself. To make another dense record rooted in rock's past, especially since punk had happened, could have sank his career. An angry, lean (for a six-piece band, that is) rock record made a lot more sense for 1978 than the '50s and '60s sounds found on the first three.

Filcman: It was. While his first two records, Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J. and The Wild, the Innocent and the E Street Shuffle have also generally topped my list of albums — in part because of the verbosity — I think it was tedious to some, making it less commercially viable while also encouraging the "new Bob Dylan" label too frequently. From the start he was a talented songwriter who could easily employ the typical elements of fiction like characters, setting and plot, but learning to edit helped him pack a punch.

Smith: He had already begun whittling things down -- there are miles of road between “Madman drummers bummers and the Indians in the summer with a teenage diplomat” and “The screen door slams, Mary’s dress sways.” I think in the three years between Born to Run and Darkness, he’d simply learned a lot. He spent a great deal of time in court, for one thing; he began listening to Hank Williams and old-time, class-conscious country music. He’d seen the films of John Ford and Howard Hawks and John Huston, and read the novels of John Steinbeck and John Dos Passos that Jon Landau had given him. The concerns of the lower-middle class became the concerns about which he began feeling most passionate, and those things are reflected in his writing, and his writing became more compact and direct as a result.

The outtakes found on Tracks and The Promise show him writing very different material than what was released on the final album. Did hearing those songs change your opinion of Darkness?

Gallucci: I don't think any of the songs changed my opinion, because many of them, especially the best tracks, sound like more chapters to the Darkness story. The songs that didn't fit remind me of the grab-bag approach used on his next album, The River.

DeRiso: While the outtakes were informative, in particular for completists, they only confirmed Bruce Springsteen’s brilliance as an editor for me. Darkness on the Edge of Town still sounds perfectly balanced.

Lifton: It didn't change my opinion of Darkness, but it changed my mind about what was going on in his mind at the time. It's easy to see those 10 songs as by a guy who's learned his lessons the hard way ("You're born with nothing and better off that way / Soon as you've got something they send someone to try and take it away"). But at the same time, he was writing all these great songs rooted in '60s pop and R&B like "Talk to Me," "Save My Love" and "Ain't Good Enough for You." The finished product only reflected one side of him. And I like the idea of Jon Landau whispering in one ear about the art of the rock album and Steven Van Zandt in the other about more hit singles.

Filcman: Yes, it gave me an even greater appreciation for his creative vision. He went through an agonizing period of writing and editing to arrive at the final product that was true to the feelings he wanted to evoke. He writes fantastic pop songs, and there are quite a few in those outtakes, but they didn't fit the theme. When you have so many songs, and great ones at that, those are tough decisions to make. Dilute the album's message or let the songs languish in the vault? But I've always felt that one of Springsteen's gifts to his fans is that he has allowed us to look back at his editing process. I've always appreciated a peak at his rewriting, and how he's not afraid to hold onto a a piece of music or lyric when he doesn't think he's done justice to it yet.

Smith: They really didn’t, just because I’d read interviews with him in the past talking about how he’d write something like “Fire” or “Rendezvous” or “Bring on the Night” and have to set them aside, because they didn’t fit the tone of the work he was recording. To hear some of those songs on Tracks and The Promise was great, and fodder for a mix disc or playlist or two of my own. The overarching thing I take away from them (and from the outtakes from The River) was just how mind-blowingly prolific a songwriter he was at the time. Like, two-albums-a-year prolific.

If you could remove one song from the finished album and replace it with one of the outtakes, which one would it be?

Gallucci: I'd take off "Factory" and replace it with "The Promise." Almost every other song on Darkness sounds epic, both in the lyrics and the music. "Factory" is a quiet, personal ode to his father that scales down the album's bigger themes. "The Promise" is way closer to what Darkness is all about. Plus, they're both slower cuts, so it would fit into that missing slot perfectly.

DeRiso: The other songs tend to feel like they were left off for a reason – because of differences in production values, because they are clearly unfinished or (quite often, actually) because upbeat tracks like “Save My Love” and “Gotta Get That Feeling" just don’t fit thematically. That said, the brilliantly ambiguous “Breakaway” might just have made the cut, if I could ever, ever decide on what other tune to delete. “Factory,” maybe? Nah.

Lifton: "The Promise" belongs on there, but, in keeping with my "two EPs" theory, he would have had to remove either "Racing in the Street" or "Darkness on the Edge of Town." That ain't happening. My least favorite track is "Streets of Fire," but I couldn't find anything better that's thematically similar to go in its place ("The Brokenhearted," "City of Night"?). So I'm gonna suggest something that's possibly sacrilegious: Apart from the drums, "Candy's Room" has never been a favorite. So I'm gonna replace it with another kinda love song, "Don't Look Back."

Filcman: There's nothing I'd replace on Darkness on the Edge of Town, but I do think "The Promise" would have made a great addition. It's among his most heartbreaking, and fits well with the tone of the record. In addition, if I had to live in a world with only one recording of "Racing in the Street," I'd surely go with the one he chose for Darkness, but the sped up recording on The Promise really hits the spot sometimes.

Smith: Hoo-boy. This is an issue, because the one I’d take out is “Candy’s Room,” and the one I’d replace it with is “Hearts of Stone,” which Springsteen gave to Southside Johnny, but which also was a standout cut on the Tracks box. First of all, there’s no real objective reason to remove “Candy’s Room”; I’ve just never cared for it. The issue is, you can’t just plop “Hearts of Stone” onto Side One in its place -- if “Candy’s Room” serves any purpose on the album, it’s to separate the two slow songs on that side (“Something in the Night” and “Racing in the Street”). Can’t close Side One of a guitar album with three ballads; that means we’d need to re-sequence the album, and then you’re really gonna piss people off. I’ll do it anyway -- move “Prove It All Night” from Side Two to “Candy”’s place on Side One -- it was a single anyway; it should go on the first side. Slot “Hearts” between “Factory” and “Streets of Fire” on Side Two. You still have two slow songs back to back, but you have two songs with relationship-centered themes leading up to the wallop of the title track to close the record. So there you go. Short question, long answer, but that’s what I’d do.

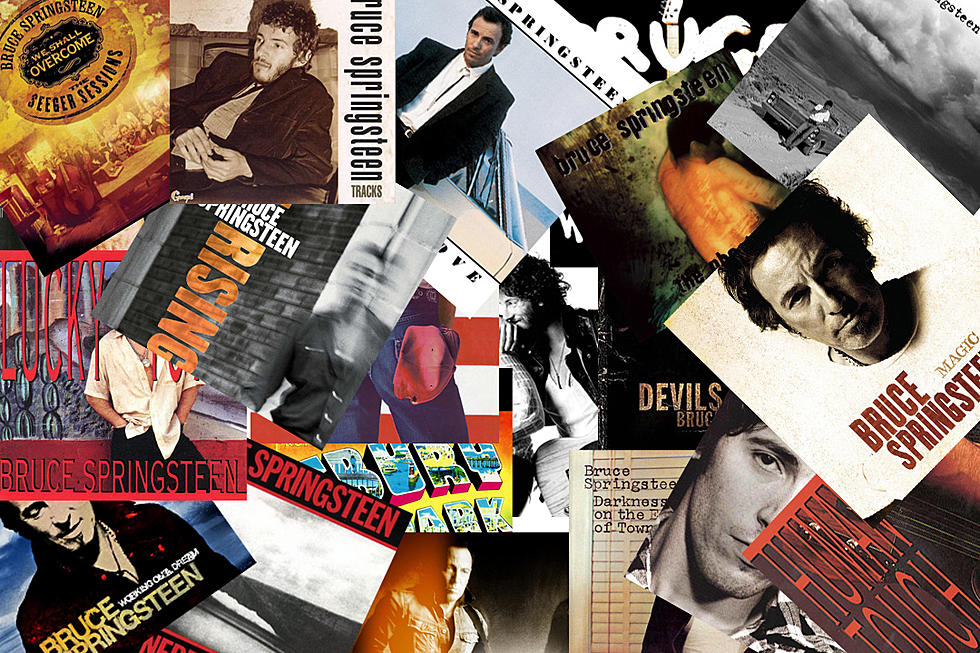

Bruce Springsteen Albums Ranked

More From 94.9 WMMQ